If you went into a laboratory with the goal of building a perfect NFL quarterback from the ground up, the end result would probably look a whole lot like Josh Allen. The University of Wyoming passer has basically every physical attribute that teams look for in a franchise signal caller: ideal size (6’5”, 223 lbs.), big hands (10⅛”), impressive athleticism (he ran a 4.75 40-yard dash and posted a 33.5” vertical jump at the NFL combine), and a Howitzer cannon for a right arm (he clocked a measured ball velocity of 62 MPH at the combine, the first quarterback to top 60 since the league began keeping track in 2008). Even in a draft class that is loaded with tantalizing quarterback prospects, Allen’s eye-popping physical gifts make him stand out from the pack. I mean, just look at this throw:

For people looking for a reason why Josh Allen of Wyoming has so much hype lately. Watch this throw. HOLY…..MOTHER….OF….MERCY. #Bears pic.twitter.com/BowWlCYpLd

— Erik Lambert (@ErikLambert1) January 4, 2017

That’s just absurd. On the run, throwing off of his back foot, Allen manages to launch the ball 45+ yards down the field and drop it square in the arms of his receiver. There are very few passers in the history of football who could have made that play. Watching plays like that, it’s not hard to see why so many scouts look at Allen and see an NFL superstar in the making. And yet, every time I hear people salivating over Allen as a potential generational talent, there is one question I keep coming back to, one that no scouting report I have read so far has provided a satisfactory answer for. To paraphrase the famous line from Moneyball: If he’s such a good quarterback, why doesn’t he play quarterback better?

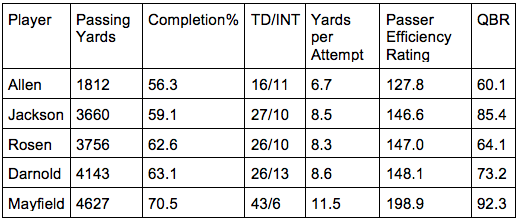

Of the five quarterbacks who are expected to be drafted in the first round this season (Allen, UCLA’s Josh Rosen, USC’s Sam Darnold, Oklahoma’s Baker Mayfield and Louisville’s Lamar Jackson), Allen was the worst statistical performer last season by almost any measure you care to use:

Oof. Allen was dead last among that group in every major statistical category in 2017, often by a fairly significant margin. And the numeric red flags don’t end with the numbers on that chart. Each of the other four quarterbacks on that list topped 300 passing yards in at least six games last season, often doing so against elite power conference competition; Allen, by contrast, did so just once, against the not-exactly-imposing Gardner-Webb Bulldogs of the Big South Conference. Allen didn’t even reach 250 yards in any other contest, and was held under 100 yards passing in three different games; of the other four passers, only Rosen had so much as one game where he failed to reach the century mark. Herein lies the paradox of Josh Allen: if you only watch his highlights, you would wonder why he isn’t considered a shoo-in for the first overall pick; if you only look at his numbers, you would wonder why any team would even consider using a first round pick on him.

I am not saying all of this to try to tear down Josh Allen, who seems like a very nice young man and who, for all I know, may indeed grow into the franchise cornerstone that many people see him as. But because Allen has become a flashpoint in the endless war of stats and data vs. eye test and gut feeling, he is the perfect example around which to frame the point I want to make: even though everyone and their mother can agree that quarterback is the most important position in football, even though we spend more time evaluating the merits of quarterbacks than every other position combined, and even though modern-day front offices enjoy an unprecedented wealth of information and film with which to make those evaluations, the NFL remains remarkably bad at defining what traits separate good quarterbacks from bad ones.

“He is gifted, in just a natural throwing motion that is so quick. With a flick of the wrist, he can get the ball just about anywhere he wants. He is a good competitor, amazingly agile and smooth and graceful in his movement as a big man can be. He handled the…offense beautifully. In a sense, it was an aerial circus.”

That’s a 1998 quote from Bill Walsh, one of the greatest offensive minds in NFL history. Walsh had been hired to scout quarterbacks by the Indianapolis Colts, who held the first overall pick in the draft and were desperate to find a passer to build their franchise around. You might assume that the young passer Walsh is raving about is Peyton Manning, whom the Colts would end selecting with the first pick…but he’s actually describing Ryan Leaf, the Washington State product who went second overall to the Chargers and was soon being described as the biggest draft bust in football history.

These days it would seem borderline cruel to compare Leaf’s career to Manning’s, but there was a time when the two were considered equally safe bets for whatever franchise ended up drafting them. In a Sports Illustrated article shortly after the draft that chronicled Colts GM Bill Polian making the difficult choice of which passer to entrust his franchise to, Peter King wrote, “Manning is more polished. Leaf throws a better deep ball. Leaf is built like a tree trunk. Manning is the ultimate student of the game. Manning is now. Leaf is the future.”

Built like a tree trunk. Throws a better deep ball. In retrospect, those qualities pale in comparison to Manning’s robotically perfect mechanics and obsessive devotion to film study, the traits that came to define his Hall of Fame career. In retrospect, you could point out that Manning obviously was a better prospect. And yet every year, scouts around the league fall madly in love with another big-armed passer who is built like a tree trunk, even if he sports massive red flags elsewhere in the scouting report (accuracy issues, interceptions, etc.). This year, that guy is Josh Allen.

This is not to say that Allen will be the next Ryan Leaf; instead, it is to say that anyone who feels absolutely certain that they have identified the next Manning (or Leaf) is giving themselves way too much credit. There is no foolproof way to project what a college quarterback will or won’t do at the next level. We still don’t know how much importance to assign to specific statistics (or any statistics) or qualities like arm strength, accuracy, or athleticism. Even professional scouts, who get paid a whole lot of money to do nothing but project the futures of college football players, routinely fall in love with specific traits in players that turn out to have little to no bearing on their success in the pros.

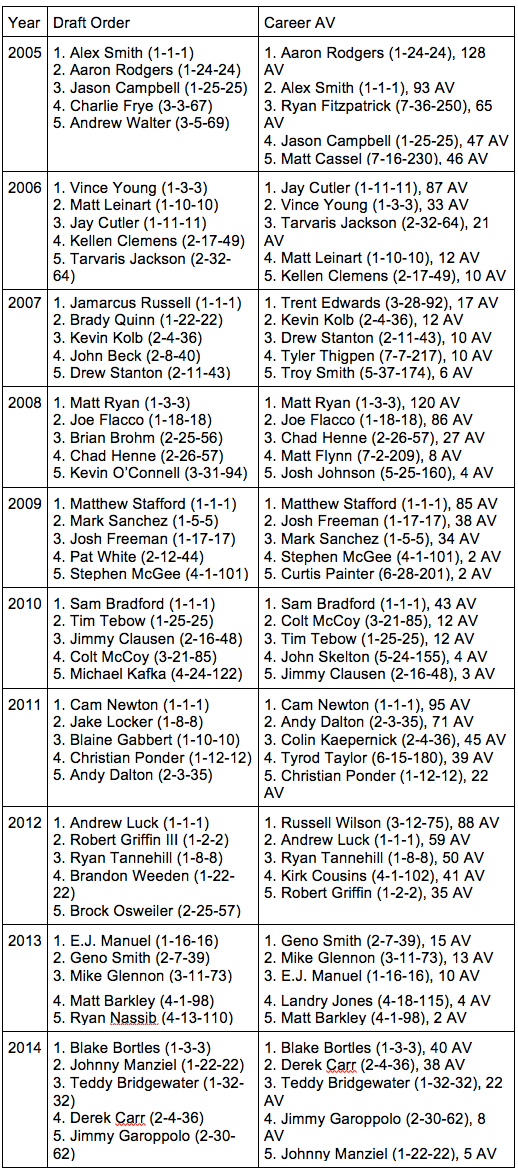

It may seem like I’m cherry-picking a particularly bad case of misjudgement with Leaf, whose career was an absolute disaster marred by attitude problems, interceptions, and questions about his commitment to the game. But recent history has shown that quarterbacks who were considered consensus first-rounders routinely turn into pumpkins under the bright lights. It’s probably still too early to pass definitive judgement on the draft classes from the last three years (2015-2017), but we can take a look at the ten years preceding that (2005-2014) to get a pretty good idea of how well the pre-draft expectations of a given year’s quarterback class has matched up to their actual production. Here is a comparison of the top five quarterbacks who were drafted in each year and the five passers who went on to have the most successful professional careers (I am ranking this second category by Pro Football Reference’s Approximate Value stat, which is a decent, if imperfect, way of measuring a player’s total career achievements without making things insanely complicated):

Each player’s draft spot is denoted as (Round-Pick in Round-Overall Pick)

That’s…not exactly an inspiring track record. And while some of those quarterback classes were just plain bad (there were no winners among the teams who drafted quarterbacks in 2007 or 2013, for example), others featured productive NFL passers who numerous teams passed over in favor of much less successful ones (reference the fact that Brock Osweiler and Brandon Weeden were drafted ahead of Russell Wilson). Also, note that because AV is a cumulative stat as opposed to a rate stat, it has a tendency to slightly overrate quarterbacks who racked up a lot of career starts–e.g., Ryan Tannehill has a better career AV than Kirk Cousins or Nick Foles because he has played in a lot more games, but I think it’s safe to say that most teams would rather have Cousins or Foles (and the same goes for Blake Bortles and Jimmy Garoppolo). All in all, it’s fair to conclude that the league-wide opinion on quarterbacking prospects has often differed wildly from the reality of what those quarterbacks became.

So why is that? Why does a league that invests so much time, money and effort in evaluating quarterbacks have such a spotty track record in doing so? Small sample size certainly plays a role—even four-year starters in college generally go to the pros with something like 1,300 college passes on film (against significantly worse competition than they will face in the NFL); and fewer and fewer potential first round quarterbacks are sticking it out for four years of school, given the massive paydays dangling in front of their noses to entice them to declare for the draft early. 1,300 passes sounds like a lot, but consider Case Keenum. Before the 2017 season, Keenum had thrown 2,229 passes in college and 777 in the NFL, and all the evidence pointed to him being an essentially replacement-level quarterback. One 3500-yard season later, and the Broncos considered him worthy of a 2-year, $36 million contract to be their anointed starter. Quarterbacks tend to develop on unpredictable trajectories, aided and/or hindered by the coaching situation and supporting cast around them, and yet scouts are expected to project the course of their entire pro careers based on just a couple seasons’ worth of college film.

There’s also the issue of the massive (and growing) schematic gap between college football and the pro game. Fewer and fewer quarterbacks are coming out of systems that are anything like what they will experience in the NFL, which makes it difficult to predict how they will fare in a complex pro-style offense. And to compound that problem, teams often fall in love with a college quarterback with a unique set of skills, only to draft him and shoehorn him into a system that doesn’t fit that skill-set at all. Think of the Titans, who drafted Marcus Mariota because of his explosive success in Oregon’s spread-out, exotic offense and then spent the last couple years square-pegging him into a conservative scheme heavy on power run plays and traditional drop-back pocket passing; is anyone surprised that his development stalled out in an offense that was designed for a completely different kind of signal caller?

In the modern age of data-driven sports analysis, the immediate reaction to any thorny issues of performance analysis is to turn to the numbers, and some people have tried to do just that. Football Outsiders (the God-Emperors of NFL number crunching) developed a stat called QBASE which tries to project the NFL careers of college quarterbacks based primarily on their completion percentage and adjusted yard per attempt, which are the statistics that they have discovered correlate most closely with NFL success. The top ten scores since 1997 (which is the earliest year for which QBASE scores have been calculated) belong to Philip Rivers, Carson Palmer, Donovan McNabb, Baker Mayfield, Russell Wilson, Peyton Manning, Marcus Mariota, Byron Leftwich, Aaron Rodgers, and Ben Roethlisberger. That’s a pretty solid list—Manning, Rodgers and Roethlisberger are among the best passers of their generation, and QBASE correctly pegged Wilson a future star even though basically no NFL scouts did—but it also includes a relative bust in Byron Leftwich. Expand to the top 20 and you will find a couple of other high-profile busts in Matt Leinart and Christian Ponder, as well as John Beck, a quarterback most people have probably forgotten about completely, who QBASE projected to be just a hair less successful at the pro level than Ben Roethlisberger. So while QBASE may be a somewhat more dependable method of evaluation than anything that has been traditionally used, it still doesn’t come close to isolating any essential truth about what separates a can’t-miss prospect from a failure.

(If you’re curious, QBASE projects Baker Mayfield to be far and away the best quarterback of this year’s class, with Rosen, Jackson and Darnold lumped fairly close together in the good-but-not-great range; by contrast, Allen would have the second-worst QBASE score of any quarterback taken in the first round since 1997, ahead of only Mark Sanchez)

So if a stat that carefully developed through years of correlation research to produce the most accurate possible predictions is still routinely churning out false conclusions, is there any hope that the NFL will ever fix its broken means of judging quarterback prospects? Probably not. Because the crux of the problem is that the traits that are most important to success at football’s most important position aren’t traits that can be properly quantified at all. They are difficult to define and impossible to measure. Think about the all-time greats at the position, the Mannings and Bradys and Montanas: what eye-popping physical abilities did they possess? None of those three had particularly strong arms; they weren’t built like tree trunks; they couldn’t throw a 70-yard deep ball or run a 4.7 40. They succeeded because they were hard-wired to handle the immense mental burden of playing quarterback, to both play on the field and see it from above. To simultaneously be the chess master and the queen. NFL GMs fall slavishly in love with raw but physically gifted passers as if they are beautiful blocks of marble that the team can carve and shape into a finished piece of art, but it seems increasingly clear that this is the wrong approach. Great quarterbacks aren’t built from the ground up; the most important ability that a starting quarterback can possess is not a learned skill at all—it’s an innate mental aptitude for the position.

We will never find a perfect way to separate good quarterback prospects from bad ones; there will always be more Ryan Leafs and Jamarcus Russells. Maybe the next one will be Josh Allen (who, in my mind, has the most red flags of any passer in this class), but it could just as easily be a guy like Mayfield who checks all the statistical boxes that Allen does not. And after the 2018 Draft next week, when five (or maybe six, if some franchise really likes Mason Rudolph) teams are crowing about how they finally have their franchise quarterback, remember that those teams really have no better idea of what they are getting than we do.

It’s not perfect but that’s why I’d rather take guys like Darnold and Allen with clear leadership qualities over others (Rosen, Mayfield) with character questions.

Mayfield is way better than both especially Allen

“way better”… okay

Interesting about Leaf.. thankfully we got Peyton.